Friday, June 19, 2009

Artist's Books - more questions

The functionality of a book pertains to its physicality; turning pages, a cover to protect it. My blog entry about my Issey Miyake book is now questionable. I didn’t consider the function of a book when designing it except as a mechanism whereby pages are turned to see new information. Is that enough consideration? Or is this 1995 quote dated? Perhaps its parameters are too confining, after all, the Book Arts Web members couldn’t come to an answer that all were happy with, (3 years after the aforementioned site) how are the rest of us supposed to?

Thursday, June 11, 2009

What is an Artist?

I’ve never seen myself as an artist. For one of my graphic design subjects we were asked to create graffiti while bearing in mind the implications of that genre. I stencilled a chimp barring his teeth in a scream and holding a globe of the world onto a 1250h x 350w mirror. It was a comment on man stuffing up the world – the chimp is laughing at us: he could have done a better job of looking after it.

1. “An artist’s book is a book made by an artist” (Donald Farren).

2. “A book whose whole entity is intended to be a work of art” (Karen Sanders).

3. “Physical or intellectual artefacts which are intended to be evaluated primarily by aesthetic, rather than utilitarian or cost criteria.” (Jane [last name unknown]

4. “Intent is everything. An Artists' book is different from other books simply because it conceived and executed from the beginning as a work of art by its creator. Nothing anyone thinks changes the original intent of the artist.” (Michael Morin)

5. “An "artist book" is an assemblage of folios, bound or otherwise, meant to be observed in a sequential fashion, either arbitrary or predetermined, and comprised of elements both textual, or pictorial. Construction is often of an importance equal to that of content. Modes of reproduction are variable, as are methods of construction.” (Michael Babcock)

6. "Artists book" is a [controversial term given to] book or book-like object in which the primary interest, or emphasis, is visual rather than textual.”

7. Artist book - A booklike structure of at least 100 pages, opened to approximately page 50, spread evenly with a gem from the recently opened can of worms and SLAMMED FORCEFULLY!!!!! until bits of gunk are evenly distributed over the book, the table, and the artist. (Preferrably within splatting distance of the urinal in the museum.) (Georgie McNeese)

To this:

“Many people, schooled and otherwise, have this hangup about "Art" and "Artists". Duchamp's urinal, mentioned earlier, proved once and for all, that art is whatever we want it to be; that any work (object, composition, dance, thought, etc) in the right situation or context (time and space) *can* be considered to transcend its fellows (other urinals, for example), or simply be sublime in its own right, and be "Art". If only one person considers it to be Art, then -- for that person -- it *is* Art, and if that person can convince sufficient others then for *all* of them it is Art. Obviously, if no one considers it Art, then it isn't.

Further, art is generally considered to be works such as painting, sculpture, musical compositions, dance, etc, therefore those who create such works are artists. If I paint, I am an artist. If I call myself an artist, no one can say with certainty otherwise. They may say I am not a good artist but that is only their opinion. If five people think I am a good artist, and five people think I'm not, then what am I? It depends upon whom you ask. Those painters who are considered to be great artists convinced sufficient others (through words or work) to be thought so. Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema used to be considered a great artist: today, most people haven't heard of him and of those who have, most consider him to have been not so great.

The long and the short of all this is that if Mary Smith calls herslf an artist, and makes what she calls artists books (with or without the apostrophe), then who is to say otherwise. Some will, of course, say she is not, or her works are not art but might be craft, or whatever, but to her friends, family, acquaintances, and maybe even some critics (remember, everyone's a critic) she is considered an Artist and what she does is considered Art. Only time will tell if it really is art, and for how long it will remain so.” (Richard Miller)

I like the way definition #6 is heading in terms of the visual being of primary interest, but it is incomplete. Books such as Window by Jeanne Baker and Green Air by Jill Morris and Lindsay Muir are created by using photographs of original artwork to illustrate the pages. Baker’s pages don’t have any text and while Morris’s do, the focus of the pages are most definitely the illustrations; but neither book could be considered to be an artist’s book.

Another thing to consider in this definition is the structure of books. Both Ed Hutchins and Emily Martin are book artists, yet the many of their works could not be described as ‘book’ or ‘book-like’. Hutchins’ Words for the World and Martin’s Vicious Circle #6 are two such examples.

One of the artist’s books I found in my research defies all the descriptions I have quoted so far: The Reál: Las Vegas, Nevada (Taylor, Mark, C. and Marquez, Jose Publisher [

By an interesting twist of fate, I found that one of the authors had participated in the Book_Arts-L listserv discussion. He had this to say (without alteration):

“I thought I'd say something about "electronic artists books" since that category has all *three* points of contention.

Last year, an artist-writer and a philosopher made a CD-ROM and called it an artists book. Apparently, it's so because then a museum published it and a big University press released it.

Since I'm one of those two crooks (the artist-writer), the recent debate on this list is pretty amusing. I mean, after the CD-ROM was done, I went out and got a press and started laying down type.

There is no trajectory as to what must happen in the future of books, nor are there absolute boundaries in art.

Personally, I feel that when I can put a small animation on a piece of paper or play a sound at the turn of a page, there won't be a need for CD-ROMs -- far cheaper to produce than die-cut jobs and offset printing, btw. It's also good to consider that books are often made to *communicate with other people.* I chose a CD-ROM over a more precious book form because I wanted to reach a large number of people, affordably, *and* I wanted to force people to use their computer for something else than looking at sports stats, stock reports, psycho gunmen games and porn.” (Jose Marquez)

The listserv discussion was in March 1998. I wonder if the people who posted on it would revise their opinions today.

Sunday, June 7, 2009

From Scroll to Codex

I have copied them here (without alteration) because they are related directly to one of ART317’s topics (topic 1) from earlier this semester and they’re an interesting read.

"Thinking About Scrolls

So, next month there will be a solo show of my books at UCLA called "Toying With Books: Playing With Conventions". I'm working on the catalog for it and I'm very excited about how it is developing. When you open the cover so it lies flat, then start pushing it towards the center, the pages start advancing one at a time. It's really nifty. And, since is has covers and the dozen individual pages are attached to one side, I guess it fits most people's definition of a book. I got the idea from a 1954 manual by Victor Strauss called "Point of Purchase Cardboard Displays". I figured I was taking a 1950's idea and updating it to the 1990's. But I was surprised when I recently showed the model to a group of colleagues. One of them, Nancy Tomasko, immediately recognized a connection between my structure and an ancient Chinese scroll. Whoa! I thought to myself, a Chinese scroll? I don't think so. The next time the group got together, Nancy presented me with a file of documentation on a particular type of Chinese scroll called a "whirlwind binding". For this type of binding, anywhere from eight to 24 additional leaves are attached to the surface of the scroll. Each sheet is indented from the previous one for easy access. What a great idea: a scroll with pages! When it was used around the 9th century, it was a very acceptable type of book. I had never seen this structure before, yet there was a definite connection between it and the 20th century book I was producing. The point I'm trying to make is that all of us who love books are operating on an historical continuum. The structure that we call a book has changed drastically from what it was in the past, and it will change drastically in the future. Other subscribers have pointed out that our word "book" pre-dates the codex, our word "library" predates the introduction of papyrus, and Richard Miller cleverly alluded to "volume" being derived from "roll", as in a scroll. Rather than being locked in time, I've found it productive to be aware of historical models and to embrace them in my development as a book artist. It's not an either/or situation. There's room on my library shelves for all kinds of books. I feel that my life and my library have both been enriched by a broad definition of what constitutes a book. Thanks to Nancy Tomasko, I am posting a selection from "The Story of Chinese Books". It traces the development of the book in China from a scroll to a sutra binding (what today we call a concertina binding) to what we now call a codex. Notice that the author identifies a modified sutra binding as a "whirlwind binding". We're not the only ones who have had trouble agreeing on definitions! For those who are interested in a further discussion of scrolls, I invite you to visit my web page. Under the heading "What is a Book?" there is an essay I originally posted to the Book Arts List on October 5, 1996 called "Is the Scroll a Book?". It a further elaboration of my continuing fascination with this ancient book structure.

Ed (Hutchins)"

"From Scrolls to Leaves

The period of the Sui and Tang dynasties, when hand copying flourished, was also the period when the scroll and rod system reached its height and when beautiful bindings appeared. In the mid-9th century, however, books in scroll form were gradually replaced by books in leaf form. The scrolls were long--often several tens of feet--and rather troublesome to unroll. The process of looking up a single sentence in the text might require the unrolling of most of a scroll. During the Warring States Period and the Qin and Han dynasties scrolls caused few problems because there were few lengthy writings. But from the Sui and Tang dynasties onward, after a number of dictionaries had been published, the matter of looking up a word or a sentence was an oft-occurring necessity. The great inconvenience and inefficiency of rolling and unrolling became more and more of a problem. Some inventive person then decided that, instead of using the scroll form, a book might be made by folding the paper to form a pile in a rectangular shape. The front and back covers of such a book were made of strong, thick paper, sometimes dyed in colour or mounted on cloth for protection. This new form was called a "leaf binding", or "sutra binding". With this new kind of binding, a reader could easily turn to any leaf to look up a word or a sentence, without having to unroll the whole book. This was a great step forward in the development of books. Before long, however, this new form was also found to have some drawbacks. A long piece of folded paper could easily become unfolded and spread out. To avoid this, book makers added another sheet of paper to the folded pile. This was creased in the middle and one half of the sheet was pasted onto the first leaf and the other half was pasted onto the last leaf. The extra sheet held the pile together and prevented it from spreading out, while the leaves of the pile could still be turned forwards and backwards. (This came to be called a "whirlwind binding".) These two forms of binding appeared in the mid-9th century. They overcame the defects of the scroll and rod system, yet they had a disadvantage in the fact that the place where the paper was folded might break after a lapse of time. Disarrangement and loss of leaves then occurred unavoidably. The next step was to bind the separate sheets into a book. When this step was taken books bound as they are today were created.

The Story of Chinese Books, written by Liu Guojun and Zheng Rusi, translated by Zhou Yicheng. Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, 1985.

Ed (Hutchins)

QUEERBOOKS"

Artist Books

I’m curious about the distinction between Art and craft.

It seems to me that the works featured at the Book Workers Guild are more ‘craft’ than they are ‘art’. (I’m referring to arts-and-crafts rather than craftsmanship, but do not intend the term to denigrate.) Where does that boundary lie? That is not to say that the final pieces are not worthy of being called Art, but the processes used to make these objects were not simply ‘painted’ or ‘sculpted’; they involved a number of crafts that when combined created the final piece. For example, a book might be covered in tanned goatskin and comprise hand-made paper, some of which are marbled (the end papers) and others screen printed. Each of the elements that are used in making the book are crafted and together they form an artist’s book and are Art: the book has meaningful content, was made by a human, is aesthetically appropriate and was intended to be a Art object by its creator.

Claire Van Vliet, The Janus Press

Based on the accordion fold, Narcissus incorporates laser printed visual as well as a Mylar mirror in which the reader virtually sees oneself on the periphery while reading. A meditative experience is presented, reading the poem before turning to the series of cloud images, then moving through layers of violet clouds, to which the words refer, ending, however, with an earth iron oxide. The box for Narcissus is covered in papers made by MacGregor-Vinzani (who also made the text paper) from colored pulp reflecting and suggesting the violet clouds referred to in the text. The box’s interior is fitted with a wooden structure that snugly houses the book’s truncated diamond shape. 24 x 29 x 1 centimeters. Created 1990.

Norma Rubovits

Marbled Vignette (no date)

Traditional marbling with watercolors on carragheen moss base.

Donald Glaister

Mark Beard,

Bound in burgundy

From Wikipedia:

A craft is a skill, especially involving practical arts.

Art is the process or product of deliberately arranging elements in a way that appeals to the senses or emotions.

Visual arts comprising fine art, decorative art, architecture and crafts

Art?

This statement, found in Drucker (and in lots of places online) intrigued me, especially as Duchamp’s urinal is so often referred to on the ART317 forum, so I decided to investigate him just enough that I got an overall gist of his philosophies. The sites I used are http://www.toutfait.com and http://www.marcelduchamp.net. In the 30 minutes I allowed myself to search these two sites I found:

He was interested in concepts of chance and metaphor, projection and eroticism as metaphor.

“Ideas such as the infra-thin, ambivalence, ambiguity, and ephemerality”

Rejected “the high seriousness prevalent in artistic circles in his own time”

“Duchamp’s views on avoiding repetition and on the irrelevance of style or the visual”

..... I'm thinking that 30 minuted is no where near sufficient for getting any sort of gist about this man's philosophies, (perhaps this site would be more succinct - for another day and more time) but I like his Art definition.

Thursday, June 4, 2009

Artist's Book

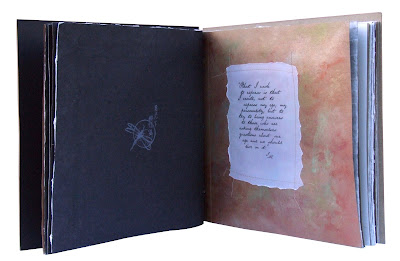

The materials used include a purchased book from which I used the cover and some pages; silk; Utee; micro beads; coloured mica powder; laser-printed images; ink; rubber stamps; fancy papers (including mulberry, vellum and form-molded); machine stitching; and transfer papers. The book is 12"x12".

The materials used include a purchased book from which I used the cover and some pages; silk; Utee; micro beads; coloured mica powder; laser-printed images; ink; rubber stamps; fancy papers (including mulberry, vellum and form-molded); machine stitching; and transfer papers. The book is 12"x12".

I scrapbook and make greeting cards so this book was somewhat a familiar territory for me in that I used or elaborated on many techniques that I was already familiar with. The degree of difficulty and finesse were above what I would go to for most of my scrapbooking endeavours and I spent considerable time tracking down materials.

I scrapbook and make greeting cards so this book was somewhat a familiar territory for me in that I used or elaborated on many techniques that I was already familiar with. The degree of difficulty and finesse were above what I would go to for most of my scrapbooking endeavours and I spent considerable time tracking down materials.

Normally when I create a scrapbook page or album I am doing so for the benefit of myself and my husband and children, or as a gift for a family member, such as grandparents. Most scrapbooking is ‘designed’ a page (or small group of pages) at a time – papers, embellishments and design elements are unique (in combination) to that page or layout and are chosen for their relationship to the photos that will be used.

Normally when I create a scrapbook page or album I am doing so for the benefit of myself and my husband and children, or as a gift for a family member, such as grandparents. Most scrapbooking is ‘designed’ a page (or small group of pages) at a time – papers, embellishments and design elements are unique (in combination) to that page or layout and are chosen for their relationship to the photos that will be used.

A slightly different approach was used here as I had a demographic to consider. Fortunately, as Miyake’s garments are so unique, and many of them could be considered more Art (there it is again!) than wearable clothes, I concluded that the audience invited to his show were of the same ilk – left-of-centre, visually oriented and creative. Miyake’s clothes beg to be touched and examined and so the catalogue has a highly textured cover piece, papers that range from embossed and rough to the feathery softness of torn mulberry, incorporates pleated silk and torn vellum, the pages are assembled with stitching that has its ends dangling, and the book is interspersed with hand-coloured pages.

Until the last few weeks I considered the catalogue to be 'craft' because of its similarity to my scrapbooking. Having read Drucker and explored quite a few books and internet sites relating to artist’s books, I think that I can change my description to Art, specifically Artist’s Book. My only difficulty now rests with self-definition. Am I a graphic designer, artist, crafter or a combination? I suppose that ultimately I am a combination of all three, with a lean towards a particular nomenclature with each creation.